The Monarch Butterfly Lifecycle

Monarch Butterflies

California is host to the Western Monarch Butterfly. Our Golden State must help to provide necessary habitat for Western Monarch butterflies to ensure the longevity of this iconic species. Let’s be worthy hosts.

Many years ago the Monarch Butterfly was designated as the National Butterfly of the U.S. – another reason to pay attention to the health of these amazing creatures.

Monarch Butterflies are often described as a keystone species because they not only respond quickly to ecological changes, but they also provide insights into the health of the broader environment they are living in.

The Great Monarch Migration

The annual Monarch migration is considered to be one of the Wonders of the Natural World. The late summer / fall migration is from northern locations – as far north as Canada – migrating south to California for the winter so that they can “overwinter” or spend the winter in a warmer climate. Overwintering sites across California are diverse and range from natural areas and public parks to state and private lands.

Then, in springtime, the Monarchs are on the move again, spreading out across a wide area to lay their eggs on the Milkweed plant and to drink nectar from flowers in California, Oregon, Washington, Idaho, Arizona, Utah and Idaho, as well as some locations in Canada.

Threat of Extinction for Monarch Butterflies

Back in the 1980s, Western Monarch Butterflies overwintered in their millions along the California coast.

By the year 2020, the population of overwintering monarch butterflies had a drastic decline to only 2000 butterflies. Reasons for this collapse in butterfly numbers include widespread pesticide use; loss of habitat; loss of breeding, feeding and overwintering grounds; loss of their only host plant (milkweed); urbanization; and changes in temperature and climate patterns. It’s important to remember that everything is interconnected; for example, warmer temperatures mean changes in plant survival rates, therefore, how much nectar is available. Climatic changes also affect how much protein there is in pollen.

Today, we are seeing the collapse of the Monarch migration and the very real likelihood of quasi-extinction occurring. This means that Western Monarchs would no longer be able to make their incredible migration.

The annual Monarch migration is an extraordinary natural event, considered to be one of the Wonders of the Natural World. In order to keep the migration alive, we must create habitat to support these amazing pollinators who can also teach us a lot about the natural world. For example, Monarch butterflies have the ability to “see” the earth’s gravitational field – their antenna contain the same magnetic properties as found in the beaks of homing pigeons!

In short, there is a great deal to learn about this iconic species, their perilous migration and their metamorphosis.

What do monarch butterflies like to eat?

Monarch butterflies are ‘generalists’ which means they will feed from any viable flowering plant. They like big open flowers that they can land on to feed. Here are some unusual and interesting facts:

- Monarch butterflies taste with their feet: They have tiny taste sensors on their feet.

- Scientists have discovered that Monarchs have favourite flavours: They will return to the same flower on repeat, remembering its flavour.

- Favorite Colors: Monarchs often like the colors red, yellow and orange.

Milkweed – the Monarch Butterfly Host Plant

Native Milkweed species are the host plants that Monarch butterflies have evolved alongside. Examples of native milkweed species are California Narrow Leaf Milkweed, Showy Milkweed, Woolly Pod Milkweed. Each milkweed species prefers a different region. The website calscape.org has native milkweed suggestions for your area of California.

Milkweed

Native Milkweed is the type that should be planted for the health of Monarch Butterflies and to support the Monarch migration. Native species of milkweed die back in wintertime and emerge fresh from the ground in springtime. This means that native species of milkweed have a much reduced level of protozoa.

Another type of milkweed is Tropical Milkweed. While the Tropical Milkweed should generally be avoided, we will include it in our discussion because it does exist (mostly originating in plant supply shops).

The main problem with Tropical Milkweed is that it harbors the parasite OE which can deform Monarch butterflies’ wings and bodies while they are still developing within their chrysalis. OE is a Protozoa parasite which sometimes lives on Milkweed. It is ingested by caterpillars when a microscopic scale from an infected butterfly drops onto a milkweed plant and is eaten by them.

Tropical Milkweed looks different: it stays evergreen and is not deciduous like the native California species of milkweed. Native species of milkweed die back in wintertime and emerge fresh from the ground in springtime. This means that native species of milkweed have a much reduced level of protozoa compared to non-native Tropical Milkweed.

Tropical Milkweed can be cut back twice a year to help lower the risk of OE infection in Monarch butterflies. It should be cut back to 6” from the ground. The best time to do this is when caterpillars have eaten all of the leaves. This way, no eggs will be destroyed, and no larvae will starve.

Planting Tropical milkweed should be avoided, and Native Milkweed should be planted for the health of Monarch Butterflies and to support the Monarch migration.

Tropical milkweed encourages winter breeding in Monarch butterflies and

It is causing Monarch butterflies to mate and lay eggs year-round. This means that fewer Western Monarch butterflies are migrating from California back north and instead deciding to stay year-round. Winter breeding leads to increased parasitism with OE. OE parasites can spread rapidly throughout Monarch populations.

If tropical milkweed is available so that multiple generations of monarchs can lay eggs on the same plants, this results in the build-up of OE spores on the milkweed leaves and the transmission of parasites to caterpillars. OE spores deposited by infected monarchs are known to persist on surfaces for a long time – several months or longer – unless they are exposed to harsh chemicals or extreme temperatures.

This photo shows a recently “eclosed” monarch butterfly beside the Tropical Milkweed that it was feeding upon as a caterpillar. This butterfly is different in that – sadly – it has malformed wings and a split proboscis (it cannot feed or fly) – this unfortunate condition is due to OE.

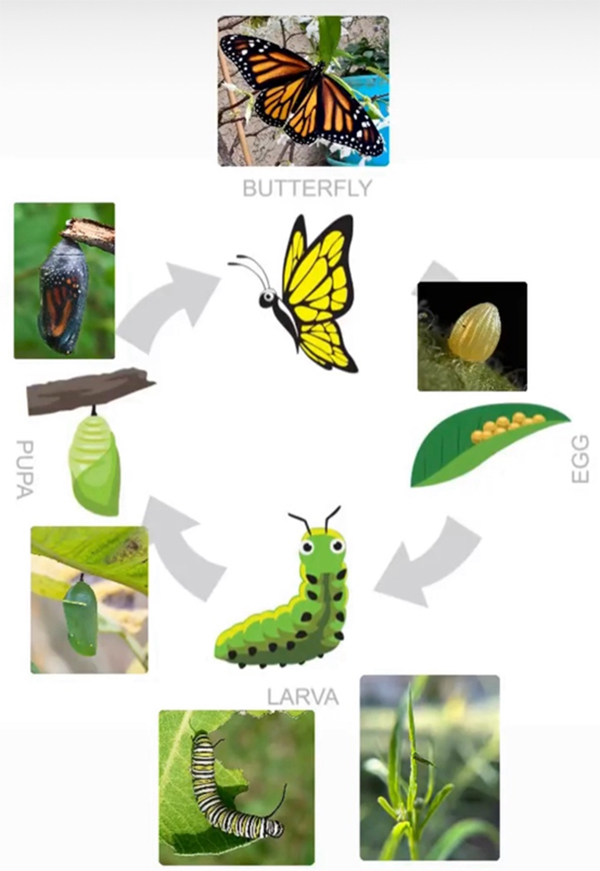

The Monarch Butterfly Lifecycle

Monarch Caterpillars are an energetic bunch! They can grow 1000 times larger than when they start out life! They eat their way, voraciously, through milkweed – their host plant. They can eat up to 20 milkweed leaves in one day, and milkweed is the only type of food they eat.

🦋 First of all, a female monarch butterfly will lay her egg on a milkweed plant. This can often be underneath the leaf – but they can turn up anywhere on a milkweed plant.

The Monarch egg is off-white with lines running down it and about the size of a pencil tip.

🐛 When the tiny caterpillar emerges from the egg, it looks like a speck of dust. It is green and absolutely minuscule!

🐛 In its first “instar” or growth stage, the tiny caterpillar starts out with black as the color of its head (and this identifying marker is only for the 1st instar).

🐛 The caterpillar will molt and shed its skin 5 times until it is a large caterpillar. When it molts, it will often find somewhere safe away from the milkweed plant to shed its skin, and will not move for a day or two. It’s important not to disturb caterpillars when they are molting.

🐛 At the 5th instar stage, the caterpillar’s antenna will be long enough that they overlap its head.

🐛 Once the caterpillar reaches its optimal size, it will leave the milkweed plant and look for a safe place to pupate and turn itself into a green chrysalis with iridescent golden markings.

🦋 After 10–14 days the chrysalis becomes transparent, and the metamorphosed butterfly’s dark body is visible. The adult emerges upside down and spends several hours drying its wings before being able to fly.

Donate to Save Pollinators

Help us create more vibrant gardens for Monarch Butterflies and native bees. Donate today!

Moths

Moths benefit plants by pollinating flowers while feeding on their nectar, and in this way they help in seed production. This not only benefits wild plants but also many of our food crops, which depend on moths as well as other insects to ensure a good harvest.

Moths are a major part of our biodiversity and play vital roles in ecosystems, affecting many other types of wildlife. Moths and their caterpillars are important food items for many other species, including amphibians, small mammals, bats and many bird species. Moth caterpillars are especially important for feeding young chicks, including those of most familiar garden birds.

Many birds eat both adult moths and their caterpillars, but the caterpillars are especially important for feeding the young.

Butterflies and moths are part of Life on Earth and an important component of our rich heritage of biodiversity.

They have been around for at least 50 million years and probably first evolved some 150 million years ago.

Here is a list of great plants for moths in Southern California

- California Fuchsia

- Salvia Gregii

- Showy Penstemon

- Coast Live Oak

- Manzanita (great for early bumble bee queens as well – this is because manzanita blooms early in the season before other plants)

- California aster

- Beach evening primrose

- Wooly blue curls

- Toyon

- Silver lupine

- Buckwheat

- Cleveland sage

- Seaside Daisy

- Climbing penstemon